Since the dawn of time, volcanoes have been key vectors of creation on earth, but also the source of considerable devastation – at times even complete extinction. In his work studying those geological wonders, remote pilot and environmental researcher Ian Godfrey has been gathering data to understand the progress of volcanic activity, and to mitigate the various destructive capacities they can inflict on communities living nearby.

Increasingly critical to his research – and safety around earth’s most volatile hot spots – are the uncrewed aerial vehicles (UAVs) and onboard tech Ian uses to get deeper into active degassing volcano craters. Those sophisticated payloads, and DJI drones in particular, also allow him to collect troves of data quicker and with reduced risk. Although the methods using UAVs are still under development they already offer insight into the understanding of volcanoes, and their importance to the planet and life on it.

Ian Godfrey at the Tenorio Volcano National park Costa Rica 2022

Ian Godfrey at the Tenorio Volcano National park Costa Rica 2022

“Despite their destructive potential, volcanoes are the foundation of life here on Earth, with their eruptions providing ash rich in minerals and nitrates that enrich surrounding soil and give rise to immense biodiversity,” said Ian. “That becomes the foundation for a wide variety of colorful flora serving as the food source for pollinators like insects, hummingbirds, and other small animals. Those in turn make up the environments for flourishing farms that feed and benefit a wide range of communities often times living far from the active volcano itself.

Academic exploration leads to career piloting drones in volcano research

Ian is a graduate from the University of South Florida with a double major in Global Business and Management. Consisting of two study abroad programs in Costa Rica and Spain to complement his classroom education in the US helped Ian understand how UAV technology could be used in various areas across the spectrum of challenging work. It was this perspective and exposure that led him to discover, embrace, and combine those two disciplines into a thriving career.

“In 2014 I visited Costa Rica on a study abroad program, and by the end of 2019 I wrote the book Investigating the Volcanoes of Costa Rica,” Ian recalls. “Following that, I began flying drones and researching how they could be used to help document the most extreme environments. With time I discovered how drones and the various payloads onboard helped relieve some of the most significant challenges, and present great opportunities in expanding our knowledge of volcanoes and their wider environmental effects.”

Greater understanding of and increased ability to coexist with volcanoes is a critical element to humanity’s future and interplanetary exploration moving forward; UAV type of aeronautical vehicles may be exploring extraterrestrial atmospheres like Venus in the near future. UAVs are already contributing to these investigations.

Ian Godfrey at the Turrialba Volcano National park Costa Rica 2022

Ian Godfrey at the Turrialba Volcano National park Costa Rica 2022

Volcano research to protect the planet and people from evolving dangers

For starters, full awareness of how volcanoes have shaped Earth’s history provides essential comprehension of how eruptions are likely to affect the future, and thereby inform the way people prepare for them. That not only includes anticipation of longer-term environmental, air quality, and climate impact, but also immediate planning to keep nearby populations and visitors away from craters once research and preventative measures indicates a looming eruption.

That is especially applicable to the millions of inhabitants and tourists who frequently visit the National Parks of Costa Rica, which issued Godfrey an exceptional special use permit to conduct drone research of its numerous volcanoes. The National Park system otherwise restricts aerial activity. The official permitting is a result from his ongoing collaboration with the Atmospheric Chemistry Laboratory of Universidad Nacional in Costa Rica begun in 2019.

When that work was temporarily paused by Covid-19 disruptions, Ian used the time productively, obtaining his Federal Aviation Administration Part 107 license allowing him to perform commercial drone activities. He also founded his Atmospheric Analytical Services company, which specializes in UAV data collection and visualization in extreme environments, and provides air quality, geographic information, and thermal IR imaging in inhospitable locations.

All of that dovetailed perfectly with the work Ian resumed once pandemic restrictions eased, and made him a more valuable partner to the various research institutions that collaborate with Atmospheric Analytical Services for different UAV projects.

Helping Costa Rica manage its volcanoes, tourists, and ambitious climate targets

Not only does the country’s economy rely heavily on tourism attracted in large part by its rain forests, beaches and volcanic areas, but it has also committed to strict decarbonization targets that can only be met by carefully calculating current and projected CO2 levels. Monitoring and researching crater behavior and volumes of gasses emitted are key to gauging carbon trajectories for the economy, but the results also contribute to the conservation efforts for protected areas within the nation.

Ian Godfrey at the Poás Volcano National park Costa Rica 2023

Ian Godfrey at the Poás Volcano National park Costa Rica 2023

Ian’s work also detects signs of evolving volcanic events, which in turn helps authorities decide when local populations and visitors may need to be cleared or kept from impact zones to ensure their safety. Given the large numbers of tourists and residents habitually present in those areas, officials depend on that precise, compelling scientific evidence of nearing eruptions in deciding when disruptive and economically costly evacuation orders must be carried out.

To offset those occasional disturbances, in addition to monitoring increased volcano activity to warn people of degassing increases or eruption risks, Ian also uses his DJI drones to assist area residents when things are calm with other contributions of unique environmental research using drones.

“We hope to continue to use drones to collect valuable environmental data used to help the communities that live nearby the active volcanoes, using multispectral cameras to monitor soil quality and search for crop invading pests,” he says. “Farmers use the volcanic slopes to cultivate a wide variety of essential agricultural crops, and by monitoring the volcanoes activity we can provide useful information to the people that have decided to live and work in these areas. We are also developing a program to teach students at Universidad Nacional how to safely and effectively operate drones in volcanic regions.”

Drones used to enter volcano craters

Getting detailed, trustworthy data on volcanic activity increasingly requires bringing measuring devises into the actual volcano crater. In many cases flying the drone down and reducing altitude rather than gaining. This type of experimentation method would not have been possible without the DJI drones to assist with the fieldwork investigation.

Mavic 3 Thermal Conducting an IR Survey of Laguna Caliente and the Active Crater

Mavic 3 Thermal Conducting an IR Survey of Laguna Caliente and the Active Crater

For starters, his Mavic 3, Mavic 3 Thermal, Mini 2, all far lighter to haul up steep and treacherous ascents toward crater areas than traditional, often manually operated measuring equipment. Other larger heavier drones such as the Matrice 600 Pro UAVs are especially helpful with lifting payloads of scientific equipment.

Extended flight ranges and battery capacities also permit his DJI drones to get up close and personal with surface areas while research teams remain at safer distances compared to earlier eras. Entry into these so-called Danger Zones previously exposed volcanologists to repertory health hazard from aerosols and acidic gases, along with potentially being exposed to an unexpected eruption.

Meantime, the diverse advantages of the different DJI drones offer a broader range of specialized capabilities for collecting data inside volcano craters near to the degassing activity. Those include valuable thermal imaging of crater terrain, and precise measurement of different kinds of gas species using the Sniffer 4D sensor from Soarability aboard certain compatible UAVs.

“Currently we are using a Matrice 600 Pro to collect water samples from Laguna Caliente – the hyper-acidic crater lake in the main active crater of the Poás volcano – and we also use this DJI drone with the Sniffer4D to take atmospheric measurements of the degassing fumaroles,” Ian says. “We use the Mavic 3 and the Mavic 3 Thermal to take short flights with the Sniffer4D and to gather IR data on known fumaroles. The Mavic 3 Thermal assists our search for previously unknown fumaroles, monitoring for increased temperatures and searching for new areas showing signs of thermal anomaly for the general safety of people visiting the National Parks.”

DJI Matrice 600 Pro Conducting Atmospheric Pollution Analysis of the Active Crater

DJI Matrice 600 Pro Conducting Atmospheric Pollution Analysis of the Active Crater

Sniffer Mapper Results of the Atmospheric Pollution Analysis of the Active Crater

Sniffer Mapper Results of the Atmospheric Pollution Analysis of the Active Crater

Ian notes that deployment of UAVs has involved a steady learning process in understanding the various ways DJI drones and onboard tech can bring back maximized results from monitored volcanoes.

Ian Godfrey & José Pablo Sibaja Brenes Operating UAVs at Poás Volcano National Park

Ian Godfrey & José Pablo Sibaja Brenes Operating UAVs at Poás Volcano National Park

“We used drones to collect data for geographic information systems and create maps; generate 3D digital models to track geomorphology of volcano craters; and lift certain scientific devices like the Sniffer4D into dangerous areas to track the volcanic degassing and identify the species of gasses being released into the atmosphere,” he says. “Thermal imaging cameras, long lasting batteries, and light weight craft are three of the most significant features we seek in drones used for volcanic and environmental data collection and visualization applications. We climb steep flanks with high altitudes, and we use these drones to monitor the active craters from various perspectives not visible to the team from our normal ground location.”

Godfrey and DJI drones: Innovative UAV research for industry advancements

Ian says the climate and topography of Costa Rica also provide frequent challenges with require a specific set of remote piloting skills, with wind gusts, humidity, and variables like turbulence inside volcanic plumes threatening to take UAVs out of commission for good.

Mavic 3 Thermal Being used at the Irazú Volcano National Park 2023

Mavic 3 Thermal Being used at the Irazú Volcano National Park 2023

During their more hazardous outings, he says, his team uses smaller drones to exploit their lighter weight, easy maneuverability, and costs that provide “a risk-reward ratio for deciding if the loss of the drone itself is worth the valuable data we could potentially collect.”

For one such mission last May, Ian says he used a DJI Mini 2 drone for a 60 meters drop into the active, degassing crater of the Turrialba volcano to collect photographical information on fumaroles inside the crater.

UAV Perspective of the Crater Floor of the Turrialba Volcano Costa Rica

UAV Perspective of the Crater Floor of the Turrialba Volcano Costa Rica

“It had never previously been accomplished and although I thought the heat of volcanic gas and ash would create conditions unbearable for the drone, we did in fact enter without any complication, documented the crater interior, and were able to return the Mini 2 to the launch station without any complications,” he recalls. “We have a fleet of drones from various companies, but when you’re working in harsh and sometimes dangerous conditions it’s important we choose the best drone able to collect the maximum amount of data in the quickest time without any delay, troubleshooting or other potential complications. For this reason, we choose DJI.”

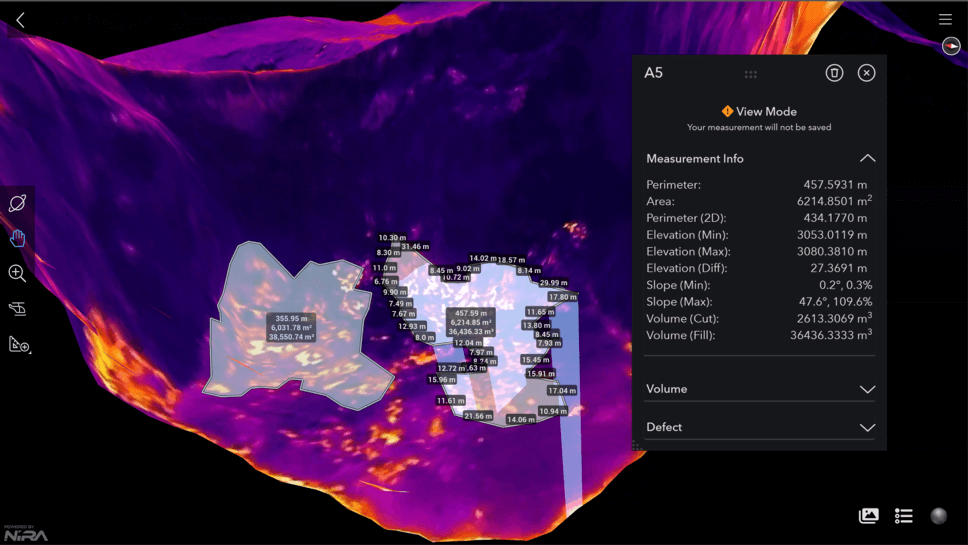

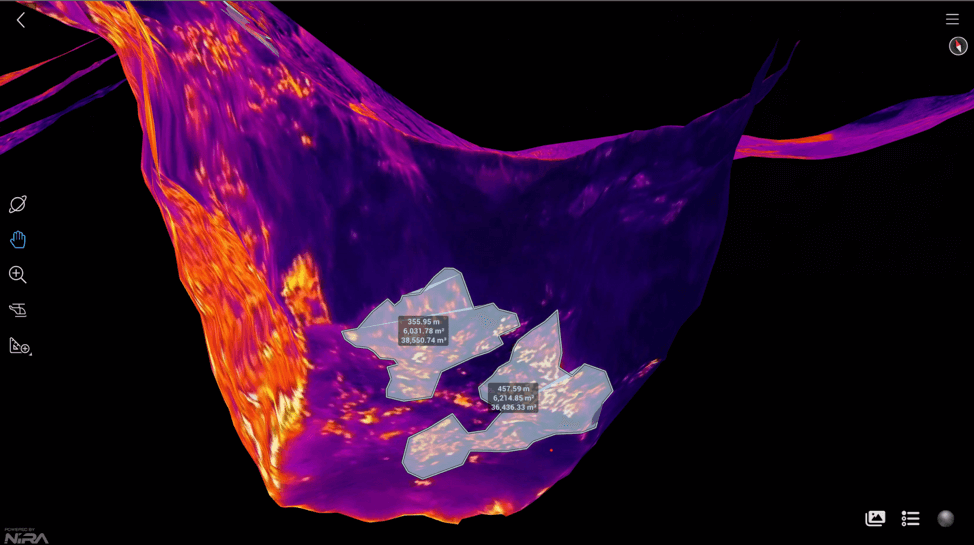

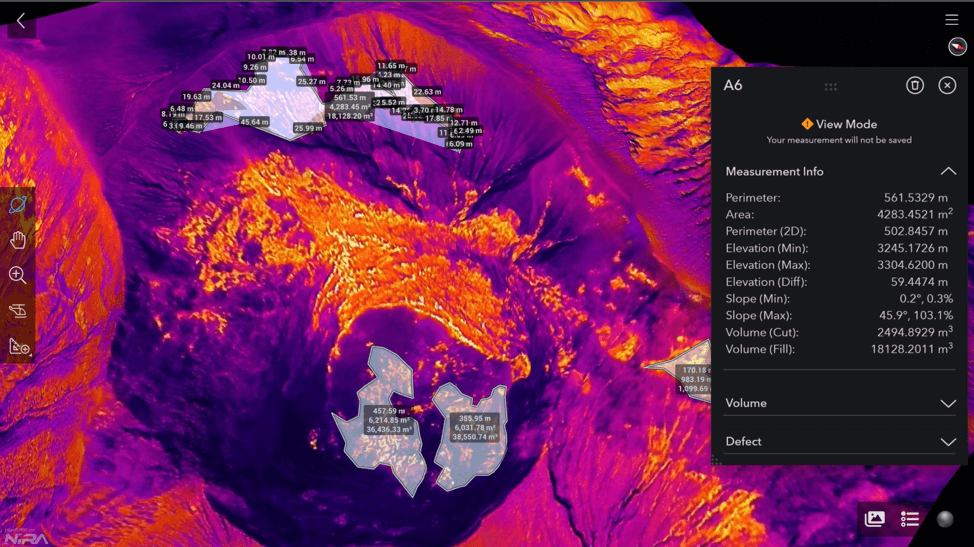

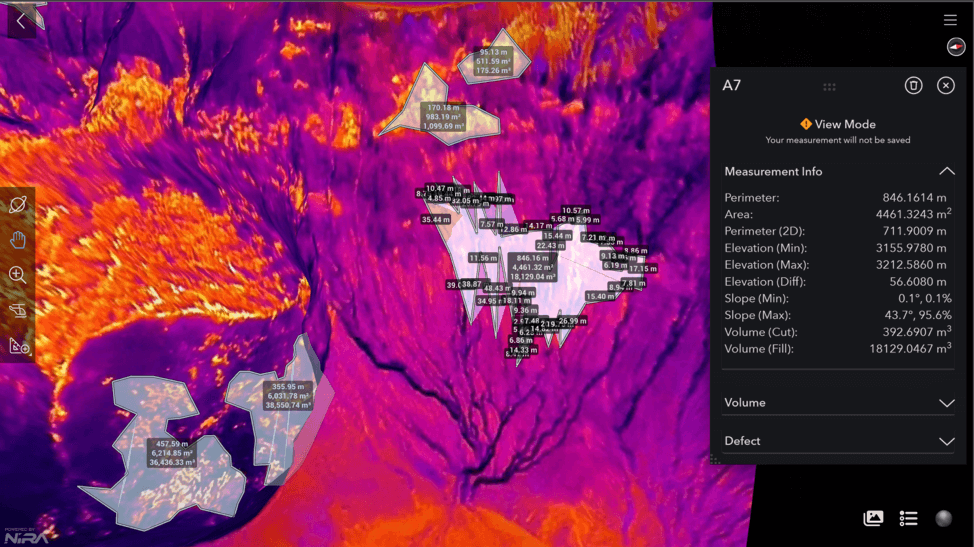

"With the images collected with drones we were able to make an interactive geo-referenced 3-D model in both RGB and IR resolution where different researchers can actually go in and take distance, depth and slope measurements around the crater. We are even able to go in and measure the perimeter of the degassing vents inside the crater.”

To find out more about Atmospheric Analytical Services, click here.

Fumarole Measurements Taken from Inside the West Crater of the Turrialba Volcano via the Digital Model Generated from IR Images taken from the DJI Mavic 3 Thermal

Fumarole Measurements Taken from Inside the West Crater of the Turrialba Volcano via the Digital Model Generated from IR Images taken from the DJI Mavic 3 Thermal

Figure 52 – Fumarole Measurements Taken from the Turrialba Digital Model Generated from IR Images taken from the DJI Mavic 3 Thermal

Figure 52 – Fumarole Measurements Taken from the Turrialba Digital Model Generated from IR Images taken from the DJI Mavic 3 Thermal